By Kimuri Mwangi

Potatoes have long been grown from tubers, especially in Africa and Kenya. But thanks to advanced technology, potato farmers from the largest potato-growing county in Kenya, Nyandarua, and other potato-growing counties now have the option of planting true hybrid potato seeds, which look like any other vegetable seeds.

Solynta, a hybrid true potato seed company based in the Netherlands, is behind the latest invention in the potato value chain. The company says they developed a (non-GMO) hybrid breeding technology platform based on the selective cross-pollination of male and female potato flowers. This ensures the generation of offspring with identical and predictable characteristics, embodying a suite of desirable traits, such as disease resistance and climate change resilience. This approach aims to ensure high, robust yield while using fewer pesticides and land.

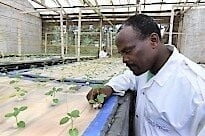

Trials for the hybrid potato seeds have been conducted with farmers in Nyandarua and Molo.

Solynta’s Director of Strategic Alliances and Business Development Charles Miller was in Nairobi recently and met our writer Kimuri Mwangi. Below is an excerpt of their interview.

Let’s start by you telling us what you are doing here.

I’m in Kenya this week to review some of the products that we have in our breeding pipeline to decide which of them we want to release with the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) so that we can provide better products to the growers in Kenya.

What is different with your potato seeds from the tubers that we have used for a long time to produce potatoes?

Solynta’s potatoes are hybrid, and using hybrid breeding we’re able to target the traits that are helpful to the growers. These could be traits that are resistant to various diseases, they could be quality traits for the tubers, and we can, by using hybrid breeding, make those adjustments in the varieties very quickly compared to traditional potato breeders.

And this is traditional hybrid so it’s non-GMO. These new varieties are delivered via true seeds, true botanical seeds, rather than tubers which are used traditionally by growers. Solynta is the developer of hybrid potatoes.

We were the first to be able to create hybrids with potatoes, and with that transformation, now we’re also able to offer botanical seeds to the growers and those come with huge benefits in our opinion.

What are the advantages of using potato seeds over tubers?

Traditionally, the potato industry uses tubers. Those tubers are bulky. They’re also perishable and that creates an extra cost and risk for growers. For example, to plant one acre of potatoes you require more than one tonne of tubers. So, you need a small truck to transport them from the tuber production areas in the West to perhaps your farm in the Central part of Kenya, and this is expensive.

With botanical seeds, think of them as seeds just like maize. They’re quite small and they can easily be stored on your kitchen table in your house, and that means that the transport cost is almost negligible. Also, you can store these seeds for many years, two to three years easily, just like you can with any vegetable seed or maize seed given the right conditions. That means that when the season is ready in your area, you can immediately plant rather than wait until the season is ready and then hope that tubers will be available for purchase.

So as Solynta and KEPHIS, we’ve been working together for three to four years to first understand the needs of the market and then bring the right products that fit those needs.

At the end of 2024, KEPHIS released three of our varieties, SOLHY 7, SOLHY 12, and SOLHY 15 for access to the market at large. These are the first true potato seed-based hybrid potatoes to be marketed, and all of Africa and Kenya can be quite proud of the forward-thinking regulators and the Ministry of Agriculture that they have here that are working to bring new products that are better for the growers as quickly as possible.

One of those varieties, SOLHY 15, has multiple genes of resistance to late blight so it’s specifically geared towards those organic farmers, toward those smaller farmers that have difficulties accessing chemicals but still have a market for potatoes in their region. If we look at these varieties, they bring high-quality tubers, which is good for consumption, they also bring reliable, stable yields.

How serious is late blight to potato farmers?

Late blight is responsible for many of the issues that are faced not just by Kenyans but globally by potato growers.

This fungus requires most growers to spray even weekly to maintain their crop, but with these new varieties, while we still recommend you spray, you can easily reduce your spray regime by 50 percent, maybe 75 percent, and still maintain a healthy disease-free crop. This means that the growers have an increased probability of stabilised yield and reduced input cost, which overall creates income stability and food security stability.

What about organic farmers? Can they look forward to using your potato seeds?

Look, this is an excellent choice for organic farmers because many of them don’t grow potatoes. Why? Because of late blight, and I can give you one good example of an organic farmer in Tigoni, a farm called Mlango Farm. In the past, and they’ve been farming for over 20 years, they have never successfully grown potatoes, but now they can grow. With this technology and with our true seeds, every week they’re delivering potatoes to the market.

What challenges are faced by potato growers that you intend to solve using the seeds?

If I think about the challenges faced by growers of potatoes in Africa and more specifically in Kenya, one of the biggest is access to quality starting material. And why is that an issue? Again, potatoes traditionally are bulky tubers. They have limited storage life, and to extend that life you need cold storage readily available, and that simply doesn’t exist in most of Africa in the scale that’s required to supply the seed necessary each season. To overcome that, we’re introducing our true potato seeds.

Again, they’re exactly like any vegetable seed, any maize seed. They’re a botanical seed. That means you can go to your local agrovet shop, you can talk to your local vegetable seed distributor, and they can access these seeds for you.

You can keep them at home and be ready to plant when your season is ready.

What good farming practices would you recommend to potato farmers?

Just to be clear, I’m not an agronomist. But I will say that with potato farming, it’s very important to maintain the quality of your land. And that means that you need to be careful of the water quality that’s put there if you have access to irrigation.

You also need to make sure that with the chemicals that are being used, you’re maintaining what is recommended by the manufacturer. Crop rotation is also quite important so that you don’t continue to grow the same crop, which may increase the disease structure that’s in your soil. And if that happens, then overall in the long term, you see reduced yields.

So, it’s about a holistic management of your farm and the products that you produce.

How has climate change affected potato growing?

Climate change is something that’s impacting all of us, and it’s impacting farmers very directly. Because I can tell you, I grew up on a farm and the climate that we face at my family’s farm is very different today than it was when I was a younger man.

And what’s necessary is that the seed industry and the chemical industry around agriculture start to truly understand the struggles that the farmers face with changing periods of rain, changing temperatures, as well as different seasons that we’re not expecting. That means that for example in potatoes, this last season should have been more wet than it was, but it was dry and warm. That means that farmers should be selecting varieties perhaps for a different type of environment than they traditionally think about. They should be much more into finding the right variety.

At Solynta, that’s one of the strong points of our hybrid breeding. We can breed very specifically for dry, warm climates for the production of better potatoes with that type of climate.

Also, as I had mentioned earlier, the late blight resistance. That is needed when you have longer periods of rainfall, which we saw one year ago in Kenya. We saw a quite extended period of cool and wet weather.

In that season, potato yields were dramatically lower across the country than they are on average. But now with the access to these new varieties, farmers can make those kinds of decisions and hopefully stabilise their yields.

Have the youth embraced the value chain?

Agriculture as a whole is struggling to attract young people into its business, let’s say, because it’s not the kind of business most people want.

They want to live in the city, work in an office, and they don’t see that as part of agriculture. But we must remember that without agriculture we don’t have food. And so, we need to find a way to attract these young people into our industry and I think there’s a really good way to do that.

In Europe we’re seeing a change now as people want to know where their food comes from. They want to be attached to the production. And by creating that awareness that, if we want quality French fries, if we want quality potato chips, then on the other side we need quality starting material for those potatoes. We need to manage the growth of those potatoes in a very reasonable and very resilient way so that we maintain the land, so that those growers can make a profit, and we can supply the high-quality food.

By creating this awareness of a system approach, then I think that starts to attract many more young people into this industry. And certainly, in Europe we’re seeing that, and it has created a true change in what we’re doing.

We even have now specific universities and specific high schools geared towards agriculture, something also that’s here in Kenya as well. And whenever I come here, I’m always happy to see how many young people are coming into agriculture. Of course we can do more, but I think we’re seeing the change here as well.

Where do you see the future of the potato sector in the next ten years?

Most of the industries in the world need to change to be more sustainable. We talked about climate change, and that impacts us every day in many different ways.

And that also means that the potato industry needs to change. One of those changes we believe at Solynta is to transform the starting material from seed tubers to true botanical seeds. We believe that this is significantly more sustainable and will bring significant benefits to all the stakeholders in the value chain.