By Kimuri Mwangi

For years, 52 acres of ancestral land in Nyakach, Kisumu County, lay unused, its boundaries forgotten and its purpose reduced to open grazing. The land, traditionally owned by local families who were not historically engaged in farming, became a source of conflict as neighbouring communities moved in with livestock.

Residents often lost animals during the confrontations, and although the establishment of an anti-stock theft police post later restored security, the land remained idle.

That changed in 2022 with the formation of the Agoro East Aggregated Farm, a community-led agroecological initiative supported under CGIAR’s Nature Positive Initiative. Through the project, 108 farmers voluntarily pooled their ancestral plots into a single, collectively managed 52-acre farm designed to restore degraded land, improve livelihoods, and build resilience to climate change.

Philip Okinyo, Chairperson of the Agoro East Aggregated Farm, speaking to Kilimo News, stated that the land had never been ploughed, except for small sections near a river where households cultivated subsistence crops such as cassava, potatoes, and beans, benefiting from the fertile alluvial soils. Over decades of grazing, plot boundaries established in 1972 disappeared, making individual ownership difficult to trace.

To address this, the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT worked with the Kisumu County Government to bring in government surveyors. The process enabled each landowner to formally identify their plot before agreeing to aggregate the land into a shared farming system.

Today, the farm operates as an integrated agroecological landscape, combining crops, livestock, water management, seed systems, and value addition. Multiple enterprises are spread across the site, reflecting principles of diversification, circular resource use, and soil regeneration.

Farmers are also being trained in dairy goat production through the Department of Dairy Technology, with preserved fodder stored on-site.

“In the past, when livestock ate all the grass, leaving the land bare, we would wait for rain to come. However, we now intercrop food crops with fodder for our animals, making it more valuable to us. Soil health is also improved by growing leguminous plants, which add nutrients naturally,” he opined.

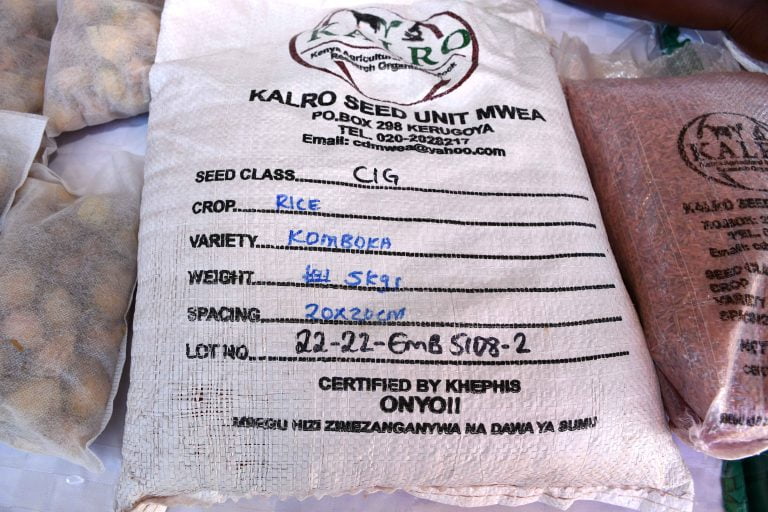

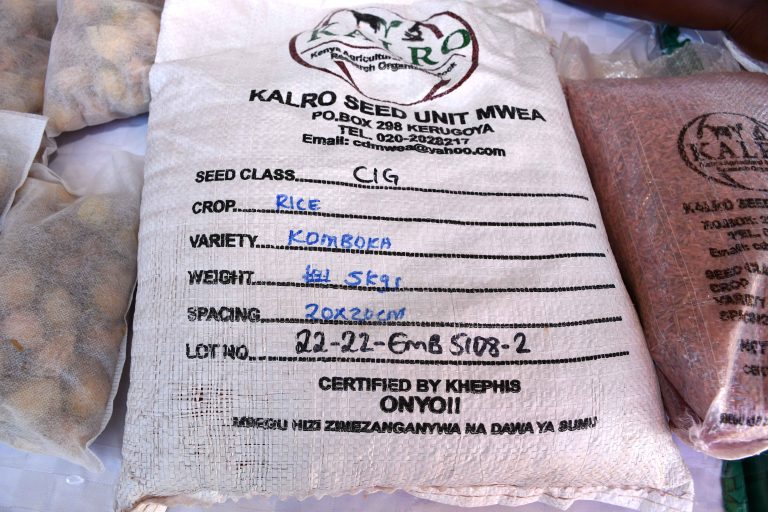

Crop diversity is a defining feature of the farm. Demonstration plots for African leafy vegetables are being established, while maize and beans are grown across several acres. KALRO has planted potatoes and vegetables for seed production rather than direct consumption. Watermelon occupies a half-acre plot, with plans to intercrop it with pawpaw, while a banana plantation, also established by KALRO, sits near a water pan. The community plans to plant more than 4,100 fruit trees, including mangoes, oranges, and pawpaw.

Livestock and aquaculture are integrated into the system to enhance nutrient recycling and income diversification. A greenhouse hosts a black soldier fly enterprise producing larvae for animal feed. A poultry house supports egg and meat production, while two fishponds, already dug, await stocking. Manure from livestock is reused to fertilise crops, reducing dependence on external inputs.

According to Okinyo, this has also changed the culture of the people. “Initially, the Luos lived along the river Nile and Lake Victoria, and their traditional occupation was simply fishing. So, when they migrated from Southern Sudan to Uganda up to this particular region, where our forefathers lived, agriculture was just done for subsistence, and so with the coming of this project, we are learning a lot that can benefit us through agriculture. From the various trainings we’ve held, we have been capacity built and the knowledge we’ve got, we can plough some back into the farm here and at our home farms. And in the end, we shall end up being giant farmers.”

Water management has been critical in addressing both droughts and floods, which have repeatedly affected Nyakach. The International Water Management Institute (IWMI) drilled a borehole and installed a 20,000-litre water tower, with plans underway to expand irrigation across the farm. Two water pans were dug to conserve water during rainy seasons and mitigate flooding, which previously wiped out harvests. Deep drainage trenches divert excess water away from crop fields.

Seed sovereignty is another cornerstone of the project. Farmers grow traditional and climate-adapted varieties sourced from the nearby Kabudi Agoro Community Seed Bank, supported by CGIAR partners including the Alliance of Bioversity International, CIAT, and ICARDA. These seeds, once common but increasingly rare, are valued for their resilience to droughts and floods.

Carlo Fadda, Research Lead on Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, said the aggregated farm was conceived as a response to land fragmentation, climate stress, and declining livelihoods. By pooling land, farmers can create economies of scale, generate ecosystem services, and make biodiversity a central pillar of production.

Fadda said the farm was co-designed with farmers through extensive dialogue, acknowledging the sensitivity of land ownership in Kenya. The system integrates crops, trees, livestock, insects, and water infrastructure to restore degraded soils and increase resilience.

“In this big farm, you can create economies of scale, you can also create ecosystem services and use biodiversity, which in our mind is one of the main pillars for the nature-positive sustainability of these farms. We started discussing this with the farmers, and it was very complicated, as you can imagine, because land is a very critical issue in Kenya. And so, to convince farmers to give up the decision-making on their land and to take a collective action for this farm to be managed jointly was a big task. A lot of workshops and conversations were involved because we wanted this to be a large agroecological farm in Western Kenya that could be a model for the county and the country,” added Fadda.

He added that diversification across value chains, including vegetables, fruits, cereals, poultry, fish, goats, and value-added products such as composite flours, is essential for economic viability. Farmers are organised into specialised groups managing different enterprises, each with its own bank account to track costs and benefits.

The farm operates through a registered marketing cooperative. Produce is sold collectively, revenues banked, and surplus profits returned to members as dividends. Women play a central role, particularly in value addition and vegetable production.

However, it has not been all rosy as Fadda points out. “We started this one year ago, and the area was really in bad shape; it was very dry. It was overgrazed and very difficult to regenerate, and the first time we started ploughing the soil, you could see big rocks coming out, which made planting very difficult. The first planting season was a failure, and this is the second time we are planting, and it’s already much better. You can see some greens coming up despite a very difficult season since there was almost no rain in this area for quite some time, but thanks to the irrigation system, some of the plants are still thriving and growing. Some crops are struggling, but it’s also a joint learning for the farmers and us on how we can manage this area much better in the future. One thing, we need more water because we want this farm to produce twice a year, and it needs to be economically viable. It’s not a joke because it needs to bring money for the farmers, for the community. It also needs to bring safe and healthy food because we are not using damaging chemicals for the consumers who are going to buy from here.”

Beyond Agoro East, the initiative also aligns with Kisumu County’s broader climate change strategy. Beatrice Okello, Senior Climate Change Officer in the county government, said Kisumu is experiencing extreme heat, unpredictable rainfall, floods, and droughts, which have reduced crop yields and affected public health, especially among women and children.

She said the county is working with the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT to promote adaptation and mitigation measures that reduce heat stress and sequester carbon, including agroforestry, integrated farming systems, and the restoration of degraded land.

Okello said in Nyakach, they have seed banks and integrated farms where farmers grow diverse crops that can survive extreme weather, citing millet, sorghum, and cassava as key food security crops.

The county has supported aggregated farms as farmer learning sites, where demonstrations are conducted on soil fertility management, agroforestry, fish farming, poultry, and alternative livelihoods such as beekeeping. These initiatives are part of a wider nature-positive solutions programme being implemented in Nyakach, with plans to replicate it in Seme and Muhoroni sub-counties.

In Seme sub-county, five women’s groups with ages ranging between 25 and up to 70 years have come together into groups. “Women are the backbone of the community and society, as they are the ones who take care of the food in the family. And that is the reason why we are prioritising and focusing on the women’s groups, so that if they go to the farm, they continue producing their crops despite the weather conditions,” opined Okello.

Kisumu County is also developing an agroecology policy through public participation, working with the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT to create an enabling framework for scaling such approaches.

For the Agoro East community, the shift has gone beyond farming techniques. Zero-grazing has replaced free-range livestock keeping, improving manure availability, milk production, and animal growth rates. Training and collective learning have strengthened farmers’ capacity to apply agroecological practices both on the aggregated farm and on their home plots.

From land once degraded and contested, Agoro East has emerged as a living example of how agroecology, collective action, and county-level climate leadership can restore ecosystems, strengthen food sovereignty, and create new economic pathways in a changing climate.