The problem? Burning crop residues. Although it causes a variety of health issues and significantly raises levels of pollution, it is a common practice in India and many other countries around the world. The solution? Turn the crop residues into something useful, such as bioenergy.

The scale of the problem is huge. Around late September and October, farmers in India’s Punjab and Haryana, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh regions burn an estimated 35 million tonnes of crop waste after harvesting. Without collection, transportation or suitable storage options, burning what’s left of the crop is really the only viable option for most farmers. This practice has increased in India in recent years with the use of combine harvesters, machines that harvest grain but discard the straw.

However, burning residues is negatively impacting soils, biodiversity and air. Every winter, pollution levels spike and thick smog hangs over New Delhi. This is largely due to the burning of rice straw, combined with the exhaust fumes from heavy traffic, open fires for cooking or the burning of rubbish to keep warm.

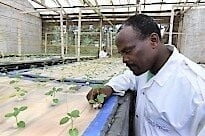

From waste products to clean energy

Rice is one of the most common crops in India, but once the rice grains are removed from the stalks, the rest of the plant is usually discarded – meaning that much of the plant itself is wasted. But these crop residues can actually be used to produce energy and biofuels. The global demand for modern forms of energy, and especially liquid biofuels, is rapidly growing, driven by environmental concerns and fluctuating oil prices.

With the problem expanding, the Government of India turned to FAO, who is now providing technical support for the development of a crop residue supply chain, so that rice straw can be collected, stored and turned into other products. For example, briquettes and pellets made from rice straw can partially replace coal in thermal power plants. Rice straw can also be used to produce compressed biogas, which could replace natural gas in transport fuel. There is also the potential for ethanol made from rice straw to be blended with petrol. These alternatives give farmers economic incentives to keep from burning the waste and contributes to the government’s aim to double farmers’ incomes.

FAO is currently assessing the most economically viable forms of bioenergy that can be produced, while also considering the potential to lower greenhouse gas emissions and reduce the country’s reliance on oil imports and coal.

Reaping the benefits

Through its Bioenergy and Food Security (BEFS) approach, FAO provides countries with the guidance, tools and support to implement bioenergy strategies in a sustainable way, with minimal impact on the environment.

Alongside India’s NITI Aayog, a central government body coordinating policy development across ministries, and its Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, a team of FAO sustainable energy experts are using the BEFS tools to identify machinery that can harvest, collect, bail and store crop residues produced in the state of Punjab.

FAO has analysed each stage of the supply chain and carried out surveys in the state of Punjab and Haryana to hear from the farmers what they think is the best way to remove the crop residues, as well as gauge their interest and expectations from the project.

With an effective business model in place and policy incentives, farmers would be better able to collect and sell residues. With FAO’s policy and technical support, the Indian government can explore setting up biogas plants to use the straw and invites private firms to do the same. Government ministries have expressed an interest in producing ethanol, compressed biogas and torrefied pellets as new sources of energy.

“Once the infrastructure is in place, using crop residues for bioenergy can bring economic benefits to the farmers who will be able to sell the straw to the private sector, diversifying their income stream and reducing air pollution at the same time. It is key that we see crop residues not as waste, but as a valuable resource that can be used for several productive purposes,” says Manas Puri, FAO’s sustainable energy expert leading the team in India.

Tomio Shichiri, FAO Representative in India, explains: “As much as 30 percent of rice residues could be converted into bioenergy and once this is tried and tested in Punjab and Haryana, we could have a model for the rest of India, not only using rice but other crop residues like sugarcane tops.”

There is no denying it: sustainable uses of crop residues for clean energy will not only reduce dependence on other carbon sources, but will also mitigate climate impacts, increase farmers’ income, reduce health hazards caused by deteriorating air quality and improve soil quality and soil biodiversity, thereby helping the country achieve its Convection on Biological Diversity targets. Clean energy can boost development, whilst protecting our planet and its precious resources. Utilizing waste products such as crop residues can help transform the agriculture sector into an ally for the environment and for farmers who can benefit from new sources of income and energy.