In 1826, the genial French gastronome Brillat-Savarin penned the phrase “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.”

Two hundred years later, pathbreaking research suggests that what we eat doesn’t just give us fuel and pleasure but also feeds the trillions of microbes in our gut microbiome, and thus constitutes one of the most consequential interactive exposures we have to our environments.

The science behind microbiome – a term used to describe the genome of all the microorganisms living in and on all vertebrates – is still in its infancy but is already helping unpack mysteries related to diet-related non-communicable diseases such as cancer and diabetes, and even to our moods. It suggests that metabolism may best be understood not as a factory process turning food into dietary energy, but a complex regulatory interface mediated by microorganisms whose function is tantamount to that of a human organ like the heart or liver.

“It’s not only about us,” says Fanette Fontaine, a microbiologist who is producing some benchmark reports for FAO on the subject. “We are walking ecosystems.”

The gut microbiome weighs as much as our brains and hosts about 1 000 different species of bacteria, with high variability as only one-sixth of these are typically found in the majority of individuals.

Thanks to the development of rapid and affordable genomic sequencing technologies, we can now identify the presence and function of a huge array of bacteria, viruses, protozoa and fungi as well as their theater of action. It turns out that many of these creatures, once feared as potentially dangerous invasive germs, perform roles that train our immune systems and influence various brain and bodily functions central to healthy lives.

It’s now clear that some gut microbiomes foster obesity – even when calorie intake wouldn’t predict it – while others correlate strongly to Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, asthma, allergies and childhood stunting.

Evidence obtained so far points quite strongly at one practical implication: we should eat more fermentable dietary fibres.

Humans cannot technically digest most dietary fibres, but gut microbes can, feeding themselves and producing beneficial small molecules (Short-Chain Fatty Acids), which serve as an important human energy source.

Highly processed foods, for example, may lack elements which ultimately impact the survival of bacterial species in our guts. “The gut is never a desert, so if you don’t feed the good guys you will have more of something else,” says Fontaine.

We each receive our first microbiome endowment from our mothers at birth. Breastfeeding also conveys specialized sugar molecules that have no nutritive function for the infant but promote the Bifidobacterium species (associated at later ages with improved metabolic signals, weight loss and less inflammation) in baby’s intestines.

When a gut microbial community is out of balance, less benign species are more likely to forage for their own survival by, for example, consuming proteins and fats instead of complex carbohydrates for energy, a process that can interfere with insulin resistance, promote unwanted fat cells and even produce carcinogenic effects. Some microbe species will even degrade the mucus barrier on our intestines, our major bastion of defense against low-grade inflammation that is common to several chronic diseases.

“Microbiome science is redefining nutrition and shows it involves more than just the nutrient composition of food,” says Karel Callens, an FAO food security expert who set up the Organization’s informal interdisciplinary microbiome team. Some key vitamins, amino acids and even neurotransmitters are important byproducts of microbial actions in our guts, he notes.

“Our lifestyle has changed faster than ever in recent decades, and our microbiome has responded much more quickly than our genome,” adds Fontaine. “The difference in pace may have disturbed the symbiotic relationship we have with our microbiome, which exacts a toll on our health.”

As our genome co-evolved with diets over millennia, increasing the diversity of plant-based food intake may bridge the gap she says.

“Microbiomes don’t have the kind of boundaries we often imagine exist,” says Callens.

That, he suggests, is why FAO’s “agri-food system” approach is well suited to assess how microbial guilds operate and how it is affected by environmental pollution and climate change.

“This research helps us better understand what healthy means,” says Anne Bogdanski, an FAO ecologist working on Climate Change, Biodiversity and the Environment. “We too are symbionts – without these little things we wouldn’t be alive.”

The microbiome approach also contributes to the One Health approach, which recognizes the fundamental and interconnected relationships between the health of people, animals, plants and the environment, she added.

We currently know far less than one percent of the different microbial species in the world – and we know more about bacteria than other types of microorganisms. However, much remains unknown about how they perform multiple and often inter-connected ecosystem functions.

For example, scientists in North America recently discovered the source of a disease killing bald eagles. A hitherto unknown, cyanobacteria was growing on an invasive aquatic weed species. The herbicide used to combat those weeds interacted with this cyanobacteria and produced a lethal fat-soluble neurotoxin that killed the bald eagles who ate these plants.

Such combinations show the hidden-but-huge role a microbiome can play in agricultural production, forestry and fisheries. Bacteria and fungi create mutualistic and reciprocally beneficial relations enabling effective nutrient absorption and plant health. As 80 percent of soil organic matter is of microbial origin, there is high potential to identify ways to restore soil carbon and healthy ecosystems.

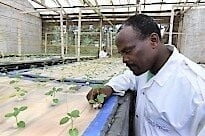

“There’s a vast field of opportunities for microbiological applications that are part of the sustainable bioeconomy,” Bogdanski adds. Understanding a microbiome can pave the way to new kinds of fertilizers, biostimulants or biopesticides to protect against certain pests. “That’s actually more of a nature-based solution than a technological one,” she says.

The microbiome isn’t a mixing bowl where you add ingredients, but a sort of “rain forest” or interactive environment of its own.

FAO has an important role in bringing microbiome science into policy debates and making sure developing countries are not left behind, Callens emphasizes. “This is about going beyond the green revolution.”