By FAO

East Africa is going through a massive desert locust infestation that’s stripping farming families of food and income and threatening the food security of millions throughout the region. And the number of locusts keeps growing. In emergencies like these, killing locusts with pesticides is a necessary evil to limit the crisis and prevent swarms from multiplying exponentially. Traditionally, chemical pesticides have been the only effective method to control extreme locust infestations. And because they work the quickest, they remain a key tool in extreme cases like the current large-scale infestations affecting the greater Horn of Africa region.

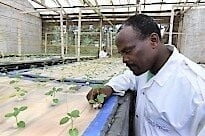

But increasingly, nature-based biopesticides offer a reliable, less harmful alternative for controlling locust outbreaks before they reach crisis levels. They also offer a solution for treating outbreaks in fragile ecosystems. “We’ve been using biopesticides to control desert locusts and it’s a great tool to treat initial, small groups of hoppers before they form huge hopper bands,” says Keith Cressman, a locust expert at FAO.

“We’re looking at an insect that multiplies 20-fold with each new generation every three months, so it’s critical that we shift our focus to interventions than can disrupt the breeding cycle. And using an effective ecological tool that farmers and governments can use in any environment makes sense in this time and age,” he notes.

How biopesticides work

As the name suggests, biopesticides repurpose nature’s own tools and use them against pests. One popular set of bio tools are microbes, meaning bacteria, fungi and viruses that affect critters. Fungi of the Metarhizium acridum family, in particular, have proven to be very effective in controlling locusts, killing hoppers and adults within a week or two. Commercial brands use this kind of fungus in their powder products. Such powders are mixed with oil and sprayed onto fields from planes or trucks. The fungus then penetrates the locust’s hard outer layer and starts feeding on the insect, sapping away its energy. The locust starts to get weaker within three days, becomes sluggish, feeds less and eventually dies.

The oil used to prepare the biopesticide is often diesel oil – although vegetable oil is also an option. But because no more than 1 litre of oil is used per hectare of land, studies of past treatment campaigns have not detected any negative environmental impacts. “Obviously, vegetable oil is a better option, but diesel seems to work better in terms of avoiding clogging of sprayers. And it is certainly far less risky to the environment still than chemical pesticides,” says Cressman.

What are the benefits?

One major benefit of biopesticides is that they are designed to target specific kinds of insects only. That means biopesticides for locust control don’t affect other “good” insects, which can continue going about their business pollinating plants and supporting the local ecosystem. What’s more, because biopesticides don’t hurt other wildlife and they have no negative effects on plants, they can be used in nature reserves, wetlands and other areas with bodies of water.

Obstacles to wider use

It’s true that biopesticides take longer to work than conventional chemicals. This means that in extreme cases, they can’t replace conventional sprays, which take less than half the number of days to kill the insect. This means that biopesticides work best in holistic control strategies that are designed to prevent, rather than cure, large-scale outbreaks. Habit and convenience are other obstacles to wider use, but neither are insurmountable, experts say.

“Many farmers are used to buying one chemical pesticide that they can use to kill multiple pests throughout the year,” says Alexandre Latchininsky, an FAO locust expert who specializes in control options. “With biopesticides, farmers need to buy different kinds of products to fight different pests, so it requires a change of habit. Additionally, biopesticides are more complicated to use, in terms of transportation, storage, and mixing. All this actually requires more training than the use of the conventional pesticides. Both specialists and the general public should be well educated on this paradigm shift from curative to preventive means.”

Prevention is becoming increasingly important with climate change, which is likely to bring more cyclones and severe rains that make for ideal breeding grounds for hoppers. The current locust crisis is a case in point. It started on the Arabian Peninsula after two cyclones in 2018, before swarms moved and multiplied rapidly throughout the region. Going forward, biopesticides have an important role to play in strategies that monitor such risky weather events and start preventive treatment in the early stages of an outbreak. This would go a long way to avoiding the kinds of large-scale crises the Horn of Africa is experiencing today and safeguard the food security of millions of people.