The Regional Centre for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD) has recently conducted assessments of wetland areas in Kenya and Uganda. Their findings underscore the importance of continued wetland monitoring in order to guard against accelerating degradation.

Wetlands are vitally important bodies of water. The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands website aptly terms them as some of the world’s most productive environments, and “Cradles of biological diversity that provide the water and productivity upon which countless species of plants and animals depend for survival.”

The function of wetlands is in cleaning the water, recharging water supplies, reducing flood risks, and providing habitats to fish and wildlife, of which many are specialist species unique to a particular wetland. Human settlements and activities also tend to converge around wetlands, given the immense potential they offer for livelihood sustainment, and as a source of food and water. Unfortunately, human activity and farming around wetlands, coupled with a changing climate, are contributing to the degradation of these important yet fragile ecosystems.

As a formal implementing partner of Digital Earth Africa, RMCRD embarked this year on a series of wetland monitoring and assessments of a large number of locations in Kenya and Uganda. This follows on from a previous mapping and monitoring of these wetlands.

Multi-disciplinary, far-reaching project

The project was a major undertaking, with the goal of gathering data and information using specialised experts and obtaining diverse perspectives, ultimately to foster collaborative innovation. Given the specialist nature of the project, RCMRD worked alongside the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) in both Kenya and Uganda, to gather together a multi-disciplinary team. Additionally, RCMRD piloted a newly-developed, modular toolkit for multi-scale wetland inventory, assessments and monitoring. This toolkit leverages established Digital Earth Africa continental scale products, services and network of users.

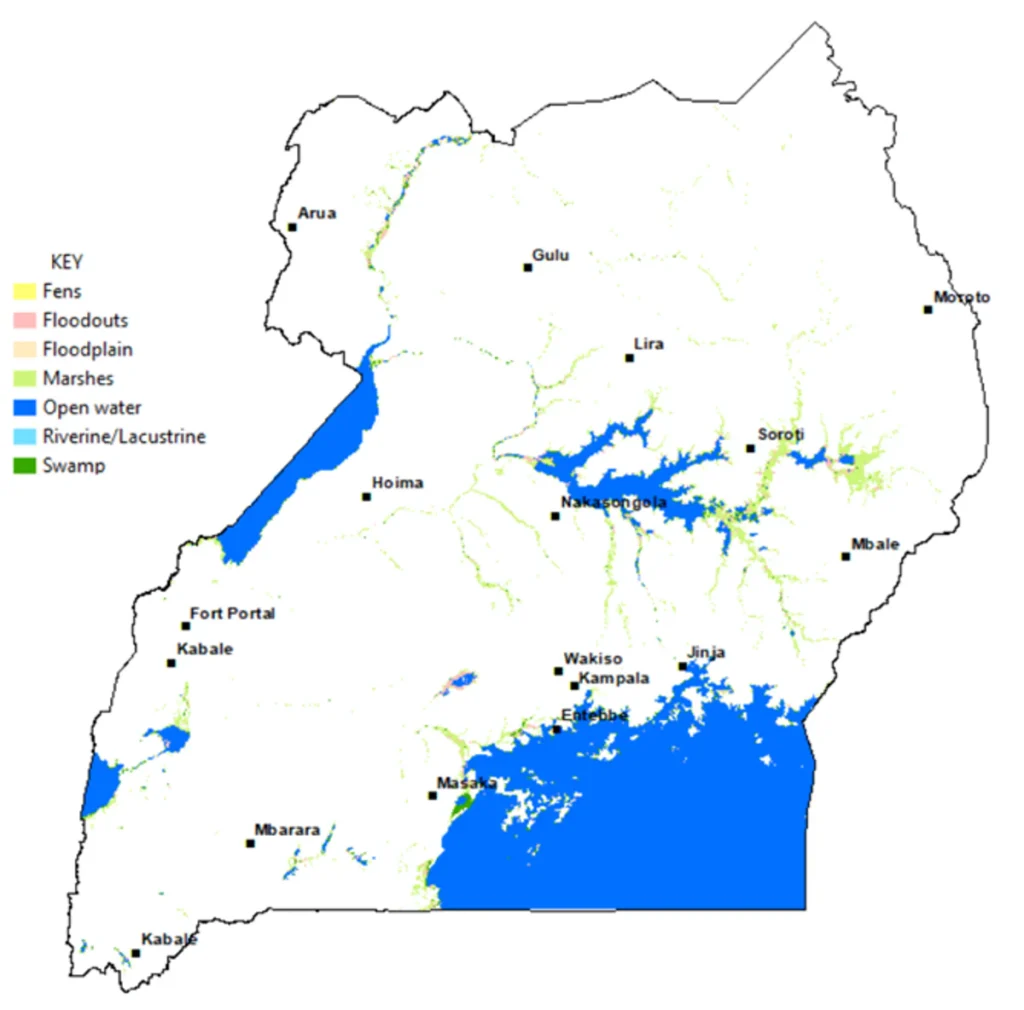

Key activities included the drafting of wetlands inventory maps for both Kenya and Uganda, utilising the Wetlands workflow notebooks available on the Digital Earth Africa Sandbox platform; the development of a data capture tool using using the Esri ArcGIS Survey 123 field data collection application (which included detail such as wetland name, type by seasonality, descriptions and photographs, and community benefits); and stakeholder interviews (including the gathering of gender-related information and perspectives from both NEMA staff and community members).

Hubs of economic activity

A myriad of activities were observed adjacent to wetlands, including human settlements, small-scale farming and commercial activities (including sugar cane and rice farming, in Uganda). As well as agriculture, fishing and pastoralism, other activities were noted such as tourism; mining (for soda ash near Lake Magadi, salt mining in Malindi, Kenya, and large-scale sand mining in Uganda); construction activities; and car washing in Uganda. These activities all contribute to a greater all lesser degree, to the depletion and pollution of the water, and reduction of wetland flora and fauna.

Many of the wetlands were seen to be highly degraded and encroached upon by communities and industrial practices. Many of the communities lacked awareness of the damage that their activities are inflicting on the wetlands. For example, car washing releases harmful detergents and oil spills from the cars into the wetland environment. In some instances, sharing sources of water with livestock can give rise to diseases in both adults and children.

In some instances, wetlands overlap with land belonging to the community or individuals, which gives rise to conflicts of usage rights and non-permissible encroachment. It is important to undertake boundary demarcations, or to be more explicit about such demarcations. For example, in Uganda NEMA has a Wetland Gazette but it does not give information on small wetlands which necessitates conducting field validation exercises.

Preservation potential with Digital Earth Africa

Following this large-scale project, which gathered a sample of 86 sample wetland points in Kenya, and a total of 279 in Uganda, RCMRD has developed a set of recommendations to ensure the sustainable management and protection of wetlands in Uganda and Kenya.

In Uganda, for example, wetland restoration is a priority for the government. Getting buy-in from the government and other stakeholders to use Digital Earth Africa’s accessible and analysis-ready tools and services, would help these stakeholders make data-driven, evidence-based decisions. Furthermore, women empowerment is high on the government agenda (specifically in Uganda). To this end, activities that seek to empower women to assess and monitor wetlands utilising user-friendly digital tools could attract government interest and support. A small grant recently awarded to RCMRD will enable the organisation to lead a pilot project of women-assessors of wetlands in urban and rural areas in Uganda and Kenya.

Partnerships and ongoing relationship building is necessary to ensure that the above opportunities are grasped. This should include working with county governments and Beach Management Units (BMUS) to integrate wetland conservation into their development plans; partnering with community-based organisations with experience in the mobilisation of communities to conserve existing wetlands and traditional indigenous knowledge; and replicating best practice community initiatives that seek to preserve biodiversity with environmentally-driven, small-scale economic activities.