By David Ndegwa

There is often a fear that if the food basket counties of Trans Nzoia, Uasin Gishu, and Nakuru were to embrace coffee farming, Kenya would face hunger. That claim is misleading, and here is why.

First, no farmer is under contract to grow food for anyone else. Farming is a business, and like any business, it makes sense to pursue the venture that brings the highest returns per acre. When you compare crops side by side, it becomes clear how irrational it is to keep growing maize in regions with high rainfall.

Take the Ruiru 11 coffee variety. At a spacing of 2m by 2.5m, one acre accommodates about 1,000 trees. By the fifth year, a well-managed tree can produce an average of 10 kilograms of cherry. At a conservative price of KShs 80 per kilogram, that translates to a gross revenue of KShs 800,000 per acre.

Comparing that with maize, even with good farming practices, an acre yields about 20 bags. At a strong price of KShs 4,000 per bag, the total is just KShs 80,000 per acre. In other words, a maize farmer would need 10 years to earn what a coffee farmer makes in a single season.

This disparity is not just a loss to farmers, but to the country as well. Choosing maize worth KShs 80,000 over coffee that generates KShs 800,000 per acre is a misallocation of resources. It makes far more sense to grow coffee on 60 per cent of the North Rift’s arable land and import maize from countries like Zambia, even if it costs more. Buying a bag at KShs 8,000 would still be more economical than producing maize locally at KShs 4,000 while sacrificing the far higher value of coffee.

The resistance to such a shift often stems from narrow thinking, sometimes even tribal considerations, instead of viewing the national outlook. If the North Rift adopted coffee farming, regions like Mt. Kenya, which already grow coffee, would not lose revenue. On the contrary, the country would gain through increased foreign exchange from higher coffee exports.

Food security can still be safeguarded by designating other regions for maize. Counties such as Makueni, Kitui, Machakos, Isiolo, and Marsabit, which are largely Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) areas, can serve as maize production zones under irrigation. Maize in these regions matures faster than in Kitale, giving them a comparative advantage.

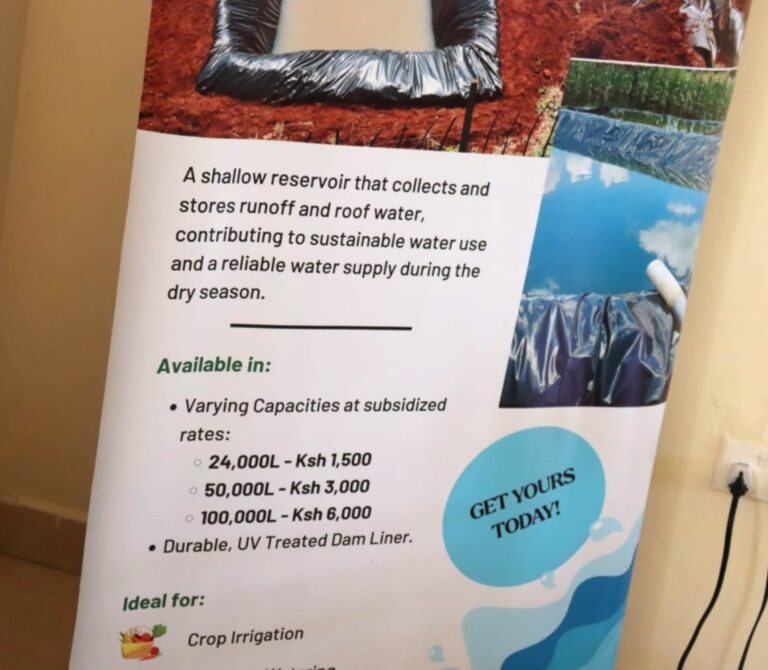

The obvious question is, where will the water come from? Kenya receives two rainy seasons every year, yet most of that water flows unused into the Indian Ocean. With proper investment in dams, the country could become water secure. Cities like Nairobi are natural catchment areas, and water harvested from the River Athi alone could irrigate vast farmland in Machakos, Makueni, and Kitui. These counties have sufficient land to produce more maize than the acreage that would shift to coffee in the North Rift.

Coffee expert Henry Kinyua will tell you that even if the entire North Rift was converted into coffee farms, the global market would still not feel the effect. Demand for coffee remains strong, and Kenya stands to gain significantly by expanding production.

So, the next time someone insists that maize is king in the North Rift, the numbers tell a different story. Coffee not only promises ten times the returns, but it also positions Kenya for greater prosperity.