By Kimuri Mwangi

After a smooth drive from Kisumu town, the tarmac gives way to a rough, dusty road leading to Nyakach. The heat is immediate and unforgiving, a reminder that this part of Kisumu County is semi-arid and increasingly hostile to conventional farming. Here, climate-smart agriculture is not a choice but a necessity.

Inside a dark, cool room that offers respite from the scorching sun, shelves are packed with thousands of seeds stored in bottles and containers. Names written boldly on jars tell stories of crops and varieties that have survived generations. This is the Kabudi-Agoro Community Seed Bank, a women-managed initiative in Nyakach that has become a critical hub for conserving indigenous, climate-adapted seeds.

The seed bank is run by women farmers drawn from the local community. According to Evelyn Okoth, the Chairlady of the Agoro–Kabudi Community Seed Bank, the initiative is both women-owned and community-driven.

“The seed bank is women-owned, and we have a total of 25 direct beneficiaries or shareholders, and we also have 83 indirect beneficiaries, but we work with them. So, the total number we have here is 108,” she said.

The seed bank was started in 2020 and officially launched in 2021 with support from the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. Its core mission is the conservation of indigenous crops that are increasingly threatened by climate change, market pressures and shifting farming practices.

Today, the seed bank holds a wide diversity of crops and varieties. These include eight indigenous maize varieties, 18 sorghum varieties, 7 finger millet varieties, 15 types of traditional leafy vegetables, and 69 varieties of beans, with plans to add more. The group also works with nuts such as groundnuts, sesame, sunflower and bambara nuts, as well as fodder crops and tree forages.

Tuber crops, including cassava, potatoes, taro and bananas, are conserved at the farm level rather than in the seed bank itself.

Beyond conservation, the Kabudi-Agoro group has expanded into organic farming inputs, producing biopesticides and biofertilizers. Okoth said, adding that members have been trained to make and use their own organic inputs, which are also sold locally.

A unique feature of the seed bank is its seed loaning system, designed to improve access for farmers who cannot afford to buy seeds or live far from markets. “We give them seeds, and we don’t sell. So, we do seed loaning whereby if we give a farmer one kilogram a farmer returns twice what we gave out, which is two kilograms,” she said.

The system also supports seed multiplication, relying on the wider community to help grow and return seeds. A governance framework that includes quality assurance officers, mobilizers and disciplinary mechanisms is also in place.

Quality control is central to the seed bank’s operations. So, how do they ensure that the seeds are viable and clean? “We have a quality assurance department, and their work is to ensure that when a seed is brought back, we check it outside, not inside. If it has pests, dirt, or chaff, the seed bank members clean it there. This also helps the farmer, because the farmer may not know how to clean it properly, so we do it there first. If we see that the seed has been destroyed, then we do not call it a seed. We take it to the store as grain for value addition or anything else,” opines the Chairlady.

Preservation relies on both traditional and modern methods. “Here, we use preservatives. We have traditional preservatives such as ash and crushed bricks as traditional ways of preservation. We also use zeolite beads, which we got from outside the country through support from the Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT. The zeolite beads can be reused many times. We put them in the seeds, and they take moisture from them. After taking the moisture, we put the beads in an oven to dry them, and then we reuse them again. This has been helping us. We also got support from ICARDA (International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas) with airtight, tightly closed jars. These jars are very tight, so no air can get in. This helps us keep our seeds clean and dry. If the seed is dried and clean and kept in the required room, it will be okay and will not be destroyed. But if it has moisture inside, it will be affected by pests,” adds Okoth.

Everything here is done procedurally to ensure that what they say is a reflection of the results from a process. Okoth explains how they conduct seed germination tests. “We do them traditionally by taking about 10 seeds and putting them in soil in a container, then watering them. If the seeds that germinate are five or seven and below, that seed is not good and is not viable. We usually require eight or more, which we call 80 percent and above. When we see that a seed is seven or below, we consider that seed not viable.”

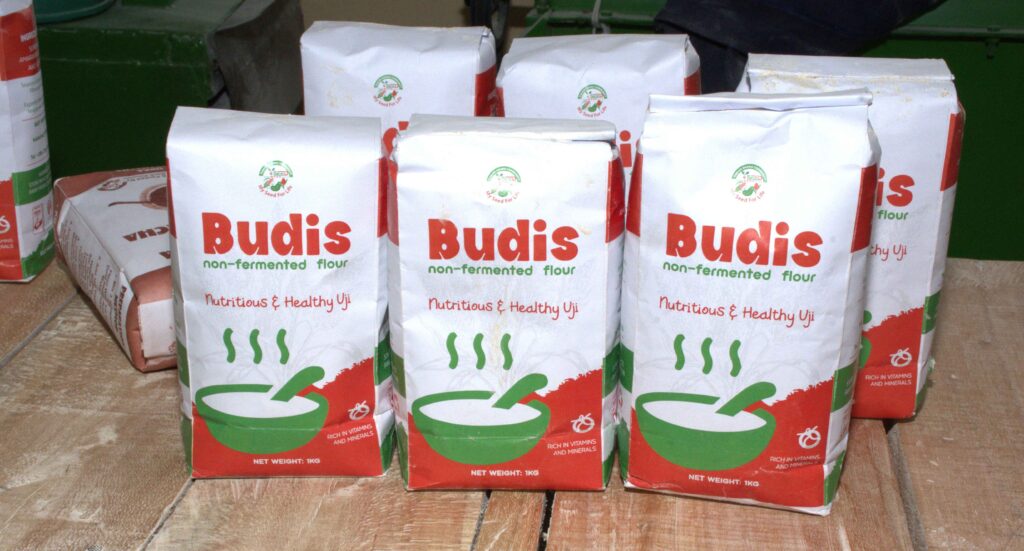

The group has also invested in value addition as a source of income, particularly for women-headed households. Using sorghum, millet, cassava and vegetables, they produce composite flours for porridge, including baby and adult formulations, as well as fermented and non-fermented products. They also process dried vegetables.

Training and equipment support have come from multiple partners, including the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, and ICARDA through the Nature Positive initiative. The group has acquired dryers, threshers, winnowers and cleaning machines that have eased labour traditionally borne by women.

While the products are already being sold locally, full commercial expansion awaits certification from the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS). Okoth confirmed that the group has begun the Kenya Bureau of Standards certification process, which will involve the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) to ensure compliance.

Climate change remains the group’s biggest challenge. Erratic rainfall and prolonged droughts have led to crop losses, even among resilient indigenous varieties. Policy constraints have also shaped the seed bank’s journey. Kenyan seed laws had restricted farmers from saving, exchanging or selling indigenous seeds. A landmark High Court ruling in December 2025 declared unconstitutional sections of the Seed and Plant Varieties Act that criminalized these practices, offering new hope for community seed banks.

Dr Carlo Fadda, Research Lead on Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, said restrictive seed laws have long undermined farmers’ livelihoods and agricultural resilience.

“The decision of the court is a major step forward because it, in principle, allows the farmers to legally use their own seeds,” he said. “It is, however, still not enough; there is still a need for an additional step, which is a new seed law that allows the farmers to actually sell those seeds,” he opined.

Fadda added that the Ministry of Agriculture is working on policy amendments that would recognize community seed banks as legitimate businesses, creating opportunities for initiatives like Kabudi-Agoro to scale up and improve livelihoods.

On the quality of the seeds, Fadda said that there should be no doubt. “The seeds that the farmers produce are of the highest standard. We don’t have them certified by KEPHIS because there are no provisions in Kenya for doing so, but, for example, in Uganda, the farmers who produce seeds in community seed banks are also registered and certified by the regulatory authority in Uganda to actually produce seeds for seed companies because they know how to produce the same quality that the company requires. So, in that sense, the community seed banks are made of highly trained and skilled farmers who can produce high-quality seeds that will germinate and are disease-free because they’ve been trained to do so, and they know how to do it.”

As demonstrated in Nyakach, women’s leadership has been central to the seed bank’s success. Women make up an estimated 80 per cent of Kenya’s agricultural labour force and play a key role in food security and seed management. According to Beatrice Okelo, Senior Climate Change Officer in the Kisumu County government, women are the backbone of the community, and the society and the county government is prioritizing projects that support women’s groups and climate-resilient crops.

As a new Seeds and Plant Varieties (Amendment) Bill, 2025, awaits debate in the Senate, Kabudi-Agoro Community Seed Bank stands as a living example of how indigenous knowledge, women’s leadership and supportive policy can converge to strengthen food security in the face of climate change.