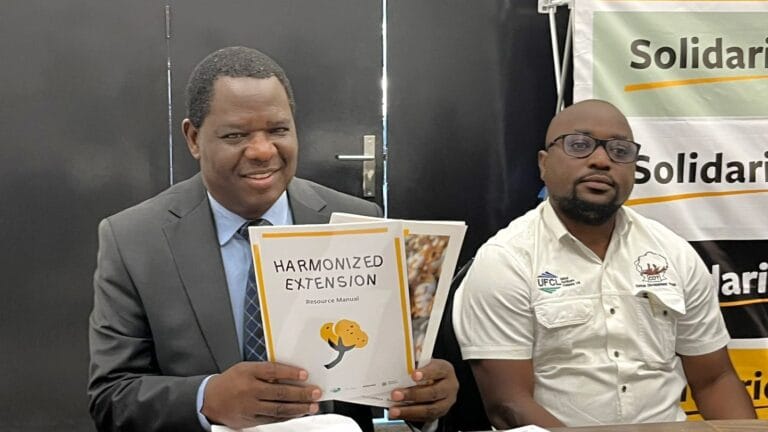

By Candice Kroutz-Kabongo, Digital Innovations Lead, Solidaridad

The future of Africa’s agricultural sector hinges on its ability to leverage data for innovation, efficiency, and resilience. Across the continent, smallholder farmers—who produce 70- 80% of the region’s food—face mounting challenges, from climate change which include but not limited to increased frequency of extreme weather events, soil degradation, loss of biodiversity and changing ecosystems; to volatile market dynamics including limited market options and very little bargaining power.

In response, digital tools and data-driven solutions have emerged as powerful catalysts for agricultural transformation. However, a critical roadblock threatens to undermine this potential: the adoption of Western-style data ownership models that prioritize individual control over collective benefit. If African governments fail to implement a collective consent approach to data governance—one that recognizes the unique realities of African agriculture—then the promise of an open data ecosystem will remain out of reach.

Unlike in Western economies, where digital literacy and widespread connectivity enable individuals to actively manage their personal data, Africa’s digital divide presents a starkly different reality. Many farmers operate in low-connectivity regions, with limited access to digital platforms or the technical know-how to navigate complex data policies. Enforcing individual consent-based models in this context risks excluding the very people who should be the primary beneficiaries of agricultural data innovations.

Instead, Africa must embrace a governance model that enables farmer cooperatives, local institutions, and trusted intermediaries to collectively manage data access and use in a way that aligns with the continent’s socio-economic realities, leveraging on social assets that fuel collective gain within the smallholder farmer sector including various forms of social capital, networks, and shared resources that enable farmers to improve productivity, resilience, and market access

The urgency of this shift cannot be overstated. With climate change accelerating risks to food security and market imbalances keeping smallholders at a disadvantage, an open data ecosystem—rooted in collective governance—can unlock efficiency gains, drive innovation, and ensures that smallholder farmers are players in this digital ecosystem, but that they get to define their collective interest and retain control over how data serves their interests. If Africa is to harness the power of data for agricultural transformation, its governments must craft policies that are context-sensitive, inclusive, and built on shared ownership rather than isolated individualism.

An open data ecosystem has the power to revolutionize Africa’s agricultural sector by addressing systemic inefficiencies that currently undermine farmer support initiatives. At present, farmer-facing organizations—ranging from government extension services to NGOs and agribusinesses—operate in silos, each gathering and managing data independently. This fragmentation leads to duplication, inefficiency, and suboptimal decision-making, ultimately failing to deliver the impact that farmers need.

One glaring inefficiency is the repetitive process of farmer registration. Many smallholder farmers are required to provide their personal and farm-related information multiple times to different organizations, each maintaining its own separate records. Not only is this an administrative burden on farmers, but it also results in inconsistent and incomplete datasets that fail to capture a farmer’s full history of engagement with support programs. Without a centralized and shared data infrastructure, organizations lack visibility into past interventions, making it difficult to tailor support effectively.

This lack of coordination extends to agricultural training and extension services, where competing organizations often deliver conflicting advice. Farmers may receive contradictory recommendations on soil management, pest control, or crop selection, leading to confusion and poor adoption of best practices. A well-integrated data system would enable farmer support organizations to align their messaging, ensuring consistency and maximizing the effectiveness of interventions. Moreover, historical data on past interventions could inform which strategies work best in different contexts, allowing for more evidence-based decision-making.

Another critical challenge is the cost of data collection. Gathering, verifying, and maintaining farmer data is an expensive process, and given the continually shrinking funding budgets, farmer support organizations must find more cost-effective and collaborative ways to manage data. Rather than duplicating efforts, organizations can pool resources and share data, reducing the financial burden while increasing the reach and impact of agricultural programs. A shared data ecosystem would allow different stakeholders—governments, NGOs, and the private sector—to leverage existing information, eliminating redundancy and directing funds towards higher-impact initiatives.

While the benefits of an open data system extend to organizations, farmers stand to gain the most from a more coordinated and transparent agricultural data ecosystem. Currently, many smallholders have little access to data that could help them make better farming and market decisions. Under a collective data governance model, farmers—either individually or through cooperatives—could access insights on market prices, climate trends, and best agricultural practices, enabling them to make informed choices about their crops, inputs, and selling strategies.

Moreover, open data could unlock new services tailored specifically to farmers’ needs. Fintech companies could use aggregated farming data to develop credit scoring models, making it easier for smallholders to access loans and insurance. Precision agriculture startups could design affordable advisory tools that use real-time data to optimize planting schedules and resource use. Rather than being passive recipients of fragmented interventions, farmers could become active participants in a digital agricultural ecosystem that works for them.

A shared data infrastructure would also enhance farmers’ bargaining power. With greater transparency in pricing, supply chains, and demand trends, smallholders would be less vulnerable to market exploitation and would have stronger leverage in negotiations with buyers and input suppliers. Additionally, cooperatives and farmer groups could use data to advocate for better government policies, resource allocation, and infrastructure investments that directly impact their livelihoods.

Beyond streamlining existing support mechanisms, an open data ecosystem could drive new waves of innovation and entrepreneurship. With better access to sector-wide insights, tech startups and agribusinesses could develop tailored digital solutions—from precision farming tools to financial services that cater to farmers’ specific needs. Governments, too, would stand to benefit, using aggregated data for more accurate policy planning, resource allocation, and climate adaptation strategies.

By embracing a collective data governance model, Africa can create an agricultural landscape where data serves as a shared asset, unlocking efficiencies, fostering collaboration, and ultimately driving sustainable growth for both farmers and the organizations that support them. However, for this to succeed, farmers must be at the center of the data revolution—ensuring that digital tools, platforms, and policies are built to empower them first and foremost.

The potential of an open data ecosystem to transform Africa’s agricultural sector is undeniable. By fostering collaboration among farmer support organizations, entrepreneurs, and governments, such a system could eliminate inefficiencies, improve farmer services, and unlock new economic opportunities. However, realizing this vision requires more than just technical innovation—it demands a policy and regulatory environment that prioritizes Africa’s unique needs.

Too often, African governments adopt data protection laws modeled after Western frameworks, prioritizing individual data ownership and strict compliance with international standards. While data security and privacy are critical, these one-size-fits-all approaches risk stifling the very innovations that could drive agricultural transformation.

Instead of being shaped by external compliance pressures, Africa’s data governance policies must be guided by the continent’s own economic, social, and agricultural realities. A collective consent model, designed to balance data protection with accessibility, would allow farmers and farmer support organizations to harness the power of shared data while ensuring that control remains in the hands of local stakeholders.

An enabling legislative environment must prioritize innovation, farmer empowerment, and sector-wide collaboration over rigid compliance. The opportunity is clear: Africa must define its own path to agricultural data governance, one that embraces collective consent, fosters innovation, and puts farmers first.

The writer Candice Kroutz-Kabongo is a Digital Innovations Lead at Solidaridad.