By Henry Kinyua

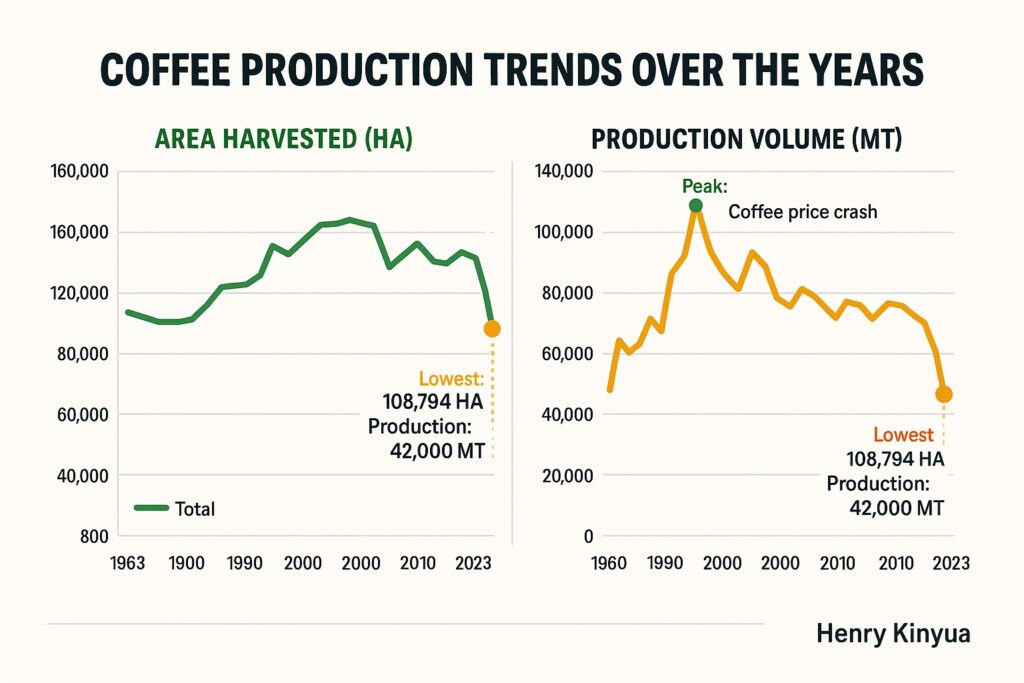

Kenya’s coffee industry has weathered dramatic highs and lows over the past six decades, with shifting fortunes in both acreage and output. Data from the Agriculture and Food Authority (AFA) – Coffee Directorate reveals that from 1962/63 to 2023, the sector experienced stark fluctuations, shaped by political, economic, and environmental factors.

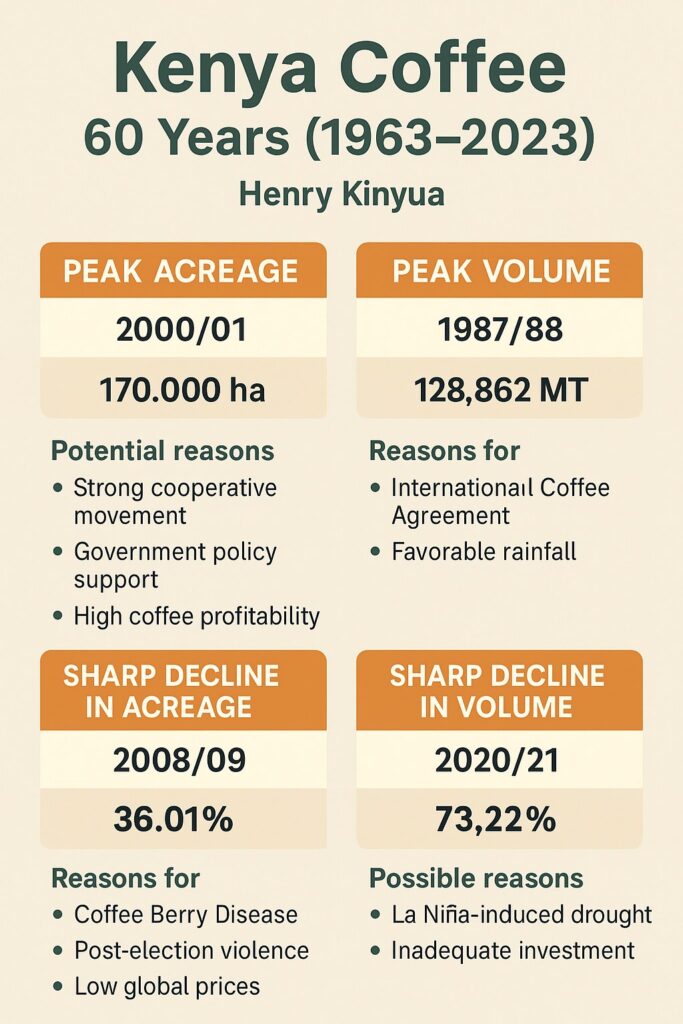

Following independence, coffee cultivation surged as farmers across the country, regardless of age or economic status, embraced the crop. Household labour sustained the early boom, especially in smallholder and estate farms. This momentum culminated in 1992/93, when coffee acreage hit a record 161,032 hectares. Peak production, however, came earlier, in the 1987/88 season, with a historic output of 128,862 metric tons.

The 1970s and 1980s marked the golden era of Kenyan coffee, with multiple strong harvests, including the 1983/84 season (128,941 MT) and the record-breaking 1987/88 output. But as the decade closed, volatility set in.

A key turning point came in 1989 with the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA), triggering a major market disruption. Production plunged from 103,839 MT in 1989/90 to 79,497 MT the following year. Although the early 2000s brought signs of recovery, with annual yields reaching over 50,000 MT from 2000 to 2004, the sector never fully regained its earlier momentum.

The most severe acreage collapse occurred between 2007/08 and 2008/09, when coffee land shrank by 33%, falling from 162,720 to 108,784 hectares. This sharp decline was driven by a combination of domestic and international crises: Kenya’s post-election violence in 2007–2008 disrupted farming communities, while the 2008 global financial crisis tightened commodity markets and dried up agricultural credit.

Weather, too, has been a persistent challenge. Coffee is highly sensitive to rainfall and temperature shifts. High-yield years like 1987/88 coincided with favourable conditions, while drought and extreme weather events—often linked to El Niño and La Niña cycles—have severely suppressed output. For instance, 2017/18 and 2019/20 saw production dip to 41,375 MT and 36,873 MT, respectively, amid prolonged dry spells across East Africa.

Long-standing structural issues have compounded these shocks. Poor marketing systems, limited financing, inadequate agricultural extension services, and mismanagement within cooperatives have further eroded the sector’s resilience.

Despite these challenges, recent years have seen renewed efforts to revitalize Kenyan coffee. Government initiatives and stakeholder engagement have sparked cautious optimism. As reforms take root, many hope the crop will once again provide a reliable livelihood for Kenya’s millions of smallholder farmers.